|

NEWS

November 2000: Two club athletes selected on Irish cross-country teams for European championships in Malmó. The king is dead - Emil Zatopek has died in Prague; 26th Nov 2000: Wade and Quinn selected for Ireland. With the retirement of Olympian Susan Smith from competitive athletics the spotlight switched to our younger athletes and they came through in fine style at the AAI Inter-county cross-country championships of Ireland on Sunday, Nov 26th, 2001 at Dungarvan to start the new millenium in the best possible manner. Club athlete Robert Wade had a great run to finish in fifth place in the individual race and so help County Waterford finish in fourth place in the inter-county contest. As a result of his high placing, Robert has been selected on the Irish panel for the upcoming European cross-country championships to be held in Malmó, Sweden on December 10th, 2001. There he will join fellow club athlete, Róisín Quinn* who has been selected on the Irish Junior women's team, despite missing last Sunday's event. Congratulations to both young athletes on this great honour and we wish them many more of the same. The scorers on the men's junior team which finished fourth overall with a total of 218 points were; Robert Wade 5th, 20.04; William Harty 9th, 20.13; James Fitzgerald 47th, 22.20; Paul Grant 49th, 22.30; Shane Power 51st, 22.33; Gavin Kennedy 57th, 22.51. The non-scorers were Dermot Cummins 65th, 23.58; Eric O'Sullivan 74th, 26.31. * Roisín was the third Irish scorer. She finished in 76th place.

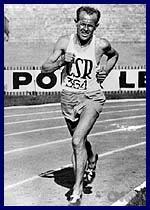

The king is dead! 22th Nov 2000: The news arrived on my desktop this morning as an official announcement from the European Athletic Association. The message was brief and to the point. The Czech

Athletic Federation informed that on 21 November 2000 the most famous

athletic hero of the Czech Republic, the great athlete and champion, EMIL

ZATOPEK, passed away in the army hospital in Prague after a short, serious

illness. Emil Zatopek died of a brain apoplexy. The day of his

funeral is not known yet, but will be held next week.

European

Athletic Association (EAA)!

Electronic Telegraph Thursday, 31 Dec, 1998. by David Miller IF THERE were a sporting fair play award for the 20th Century, one of the foremost candidates would be Emil Zatopek. The renowned Olympic champion of London '48 and Helsinki '52, from the former Czechoslovakia, is remembered for grinding out victories and multiple world records, while resembling an agonised man wrestling with an octopus on a conveyor belt. A definitive Olympian, whose deeds rank alongside Nurmi and Owens, he was, in the same manner as they, an inspiration for future generations, simultaneously revered by contemporaries such as Gordon Pirie. Fifty years after his spectacular emergence in London, and at a time when sport is battered by corruption among administrators and competitors, it is appropriate to pay tribute to a 76-year-old who personifies lost ideals. Many are aware that in 1968, protesting against Soviet tanks that rolled into Prague to quell the democratic movement led by Premier Alexander Dubcek and student martyr Jan Palac - who sacrificially burned himself to death - Zatopek was dismissed as a senior army officer and consigned for six years to pushing a shovel in the Bohemian uranium mines. He had dared to suggest that the Soviet Union should be banned from the Olympic Games in Mexico City. But the courageous act that nearly cost him his place in the 1952 Olympic team - or much worse - is still largely unknown, suppressed at the time by State-controlled media. Zatopek, then the hottest name in world sport, arrived in Helsinki three days after the rest of the team - a seemingly ordinary occurrence but one that hid an extraordinary act of humanity by Zatopek. Among a tide of young athletes striving to emulate the national hero was Stanislav Jungwirth, a gifted young 1500 metres runner. His father, however, an anti-communist activist, was a political prisoner. Jungwirth was omitted from the Olympic team. Zatopek instantly stated: "If he does not go, neither do I." Both stayed behind in Prague but such was Zatopek's global prestige, and the national expectation, that within 48 hours the Communist authorities caved in. The two departed. Though Jungwirth narrowly missed the final, he would come sixth four years later and break the world record in 1957. Zatopek was a phenomenon not just for his records and medals - gold and silver in London, uniquely three gold, including the marathon in Helsinki - but for his extreme modesty. His willpower burned intensely: outwardly, he was, and remains, so gently unassuming that it is difficult to correlate the man and the athlete. "I was not very talented, I never imagined I would succeed," he says of his early days, working as a plastics-chemistry technician in the Bata shoe factory at Zlin. His parents discouraged him from running, his father, a carpenter, in particular. "Working in the garden is enough if you want exercise," young Emil was told. Under German occupation, sport was restricted, crowds forbidden for any kind of gathering. In 1941, aged 19, Zatopek's time for 1500 metres was 4min 20sec, something bettered by British schoolboys for the longer mile. Improving slowly, in 1944 he was having to borrow some tennis shoes to continue running. Nonetheless, inside two weeks, he broke the national records for 2,000, 3,000 and 5,000m. Sceptical sports editors in Bohemian Prague telephoned to check the news being sent from rival Moravia. Even as liberating Soviet tanks bombarded Zlin and German trucks beat a vain retreat westwards, Zatopek was busy improving those records. Experts questioned the rolling head, the tortured arm action. They did not notice the perfect leg cadence, could not see the exceptional lungs. Making his first overseas flight to Oslo for the 1946 European Championships, he finished fifth behind veteran Sydney Wooderson, of Britain, in the 5,000. "What I learnt in Oslo," he recalls, "was that you must know how to run [tactically] and that you must preserve your power for the finish." The next year he ran the eighth all-time fastest 3,000, "but I still didn't feel capable of Olympic victory." Arriving at the Uxbridge men's 'Olympic village' in 1948, Zatopek trained quietly, played his guitar, and insisted on taking part in the opening ceremony in a heatwave, even though the 10,000m was the following day. Ordered to return to the village, he slipped back one place among the marching nations, mingled with the Danes, and defiantly reappeared in the arena. "You cannot send me back now," he said when confronted again, "the King is watching you." With his coach, he devised a scheme for checking his 71-second even-lap schedule. Too fast, the coach would raise a white shirt; too slow, a red one. The rival was world record holder Viljo Heino, of Finland. After eight laps, up went the red: Zatopek took the lead. Momentarily, Heino regained it, but had overshot his mark, and by 7km was overpowered. Zatopek had set a new Olympic record of 29-59.6 with Alain Mimoun, of France, a distant second. For the 5,000, the formidable Gaston Reiff, of Belgium, and Wim Slijkhuis, of Holland, were the danger. The three forged a gruelling battle with Zatopek trailing into the last lap. Slijkhuis faltered. The grimacing Czech went by. Reiff, 20 yards ahead, anxiously glanced back as the crowd's roar rose. By a metre, Reiff got home. By now Zatopek had met and married Dana Ingrova a promising young javelin thrower. In the spring of 1949 they went to the Soviet training camp on the Black Sea. "I think they [the Soviet athletes]wanted to see what I was doing," Zatopek says, with a sly smile. It was a frightening daily schedule of 20 x 200, 40 x 400 - the same endurance built on speed that Sebastian Coe would successfully employ 25 years later. In 1949 came the first world record, 29-28.2 for 10km, lowering Heino's time. Heino duly regained the record. Zatopek lowered it twice more, adding the 10-mile, 20km and one hour records for good measure. The next Olympic year [1952] began badly. Running with a virus to "bolster" a minor event he became seriously ill. The team doctor said he should rest for three months or risk damaging his heart. There were only six weeks to Helsinki. He provocatively decided to cure himself: with tea and fresh lemons. Recovering, he ran in Budapest and Kiev, winning in times slow enough to cause national anxiety. "Yet by the time I arrived, I was healthy," he recalls. "I was record-holder and defending champion for 10km, so I didn't feel too worried, even if not in peak condition." Up in the stands, the legendary Nurmi and Kolehmainen were watching. Once again Zatopek decided to destroy the field with even pace. By halfway, Pirie was out of contention. In the 18th lap a surge finally left Mimoun gasping. Again a new Olympic record. Years later, Zatopek magnaminously gave his medal to Ron Clarke of Australia, deprived by the heat of Mexico. And now the 5,000. "It was," he reflects, "the best finish I ever had, and against great rivals: Schade, of Germany, who was favourite, Mimoun, Pirie and Chataway, of Britain. I'd calculated to win on the last lap but when three of them went past me I thought it was all over." After 2km, Zatopek took the lead from Schade, who was running at the front out of fear. "Herbert, do two laps with me," Zatopek said, side by side, remarkably attempting to ease the pressure on someone he knew could beat him. But Schade sprinted clear, only to fade after 3km. At the bell, Chataway, Schade and Mimoun all went past. They had gone too early. "I was experienced enough to know that sprinting produces quick fatigue. First Chataway fell, then Schade gave up, and I knew Mimoun could not last. So it gave me a chance for a second kick." To crown the satisfaction, Dana had just won the women's javelin. Now the marathon, his first ever. The old man smiles. "The marathon is not a very difficult race. Other races are all about speed. The marathon is about [aerobic] rate of recovery. Jim Peters, of Britain, was favourite, but running without control. In the marathon, control is everything. Having the one-hour record, I'd felt I might do all right." He did indeed. Peters collapsed at 37km. Zatopek won, peeling off his blood-stained shoes before the next man had entered the stadium. We may not see his like again.

A tribute to my 'runner of the century' by Mike Sandrock There have been many end-of-the-millennium lists of the world's greatest athletes. For me, naming the runner of the century is easy: Emil Zatopek, a former Czech Army colonel and four-time Olympic gold medalist who revolutionized the way runners train. In Zatopek, called "the immortal Czech" or "the human locomotive," are summed up all the best qualities of an athlete: an inexorable will to win combined with an extraordinary sensitivity to others. He is a true humanist, an internationalist whose life shows how it's possible to break down the borders that often separate people. I had heard stories about Zatopek for years and first met him in person about a decade ago. The stories handed down from runner to runner are numerous and so astounding as to seem apocryphal: He did his laundry by filling his bathtub with suds and running in place; he trained by carrying his wife, Dana, on his back; he bounded through the woods outside Prague wearing Army boots, and he did 100x400-meter repeats every day for a week. Zatopek won a gold medal in the 1948 London 10,000 meters. Four years later, he made history in Helsinki, winning the 5,000- and 10,000-meter events, then taking the gold and setting the Olympic record in his first marathon ever. That triple has not been equaled. It is not, however, his gold medals or 18 world records that make Zatopek special. Rather, it is his approach to running, and more importantly, to life. At events he was the center of attention. He spoke several languages, allowing athletes from around the world to get to know one other and thus overcome stereotypes and become friends. It was, and still is, friendship that Zatopek values most. In 1966, he gave his 1952 10,000-meter gold medal to Ron Clarke, the Australian great who never won a gold. When I visited Emil in Prague, he talked of the special bond among runners. That, he said, is more important than any medal or record. "With all their energy, everybody tries to do their best," Zatopek, now 77, said. "This struggle, it stays very deep in your mind. And it produces great respect among adversaries...It is really what I have high esteem for, this friendship in sport." Perhaps Clarke put it best when he said of Zatopek: "His enthusiasm, his friendliness, his love of life, shone through every movement. There is not, and never was, a greater man than Emil Zatopek." December 27, 1999

|